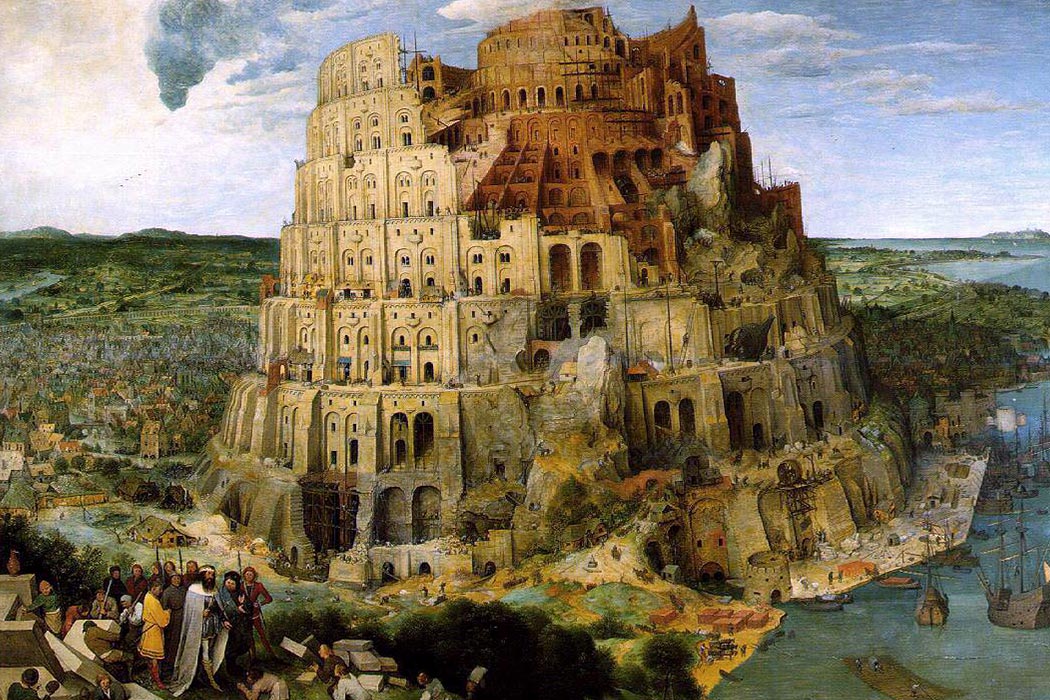

Conlang Guide

What is a conlang?

A constructed language (conlang for short) is a consciously created language, as opposed to a language developed naturally (also known as a natlang). There's a lot of complicated nuance in what it means to be a conlang, but very briefly, there are three basic categories of conlang: engineered, auxlang, and artlang. An engineered language exists basically as an experiment in some form of logic, philosophy, or linguistics. An auxlang (international auxiliary language) is used to facilitate international communication, so it'd be something like Esperanto. But it's really artlangs (artistic language) that I'm going to be focusing on today.

Artlangs are created "for aesthetic pleasure or humorous effect" (as defined by wikipedia), and include languages constructed for worlds! Most of us worldbuilders will make conlangs that are meant to be natlangs in a fictional world, but you could also make a language for no particular reason and the term would still apply. My first conlang (which still looks and sounds horrible, lol) was actually an artlang meant to be an auxlang in universe in a fictional world.

Conlangs are distinct from cyphers, codes, and sometimes even the scattered fake words you find in a story, because they are able to express meaning in their own way, separate from any existing language. They can, of course, be based upon, similar to, or even derived from natural languages, but not in any way a one to one direct comparison. They typically have their own grammar, syllabic structure, phraseology, and sounds.

Step one in making a conlang

Most hard and fast "rules" for conlanging or worldbuilding or creative writing in general are pretty bullshit, in my opinion, but for a conlang, the very first thing you always have to do is pick a set of sounds. There's kind of no working your way around it. You might think, "so 28 sounds like the 28 letters we have in English, right?" Because that's what I thought in my first one, lol, but there are actually

44 sounds in English, and there are essentially an unlimited amount of possible sounds you could use for your language that do not exist in English if you include tones, accents, and other noises like tooth gnashing or whistles or clicks. The most common ones found in our natural languages are included and represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet, and I would recommend you stick to those that you can pronounce (even if it's not perfectly easy at first) for your first couple conlangs.

Particularly, I love this link

IPA Chart, which gives you audio clips of each IPA symbol, as me trying to explain them all to you would be... insane.

What I

would suggest is listen for lots of different kinds of sounds! Find languages that sound really different from yours. Listen to youtube videos of people speaking in foreign languages or conlangs and try to identify them in the IPA chart. Listen to the IPA sounds in different contexts (the wikipedia sound clips and the link I sent above sometimes sound very different for the same symbols). Consider modifications to sounds you're familiar with. Did you know there are like, four different sounds people still refer to as "r"? The English "r" is so unusual in languages that there's basically nothing that sounds more English. It's a lot more common to hear an "r" that's kind of tapped, somewhere between an "l" and a "d." And then of course there's the rolled "r," and the French "r" which sounds pretty similar to a letter in Arabic! Or in Korean, letters aren't fully pronounced at the end stop of a syllable (if there's no vowel immediately after it), so instead of saying "pe-tuh" the way we do with "pet," they'd just end it with the tongue in the "t" position. Na'vi features somewhat rarer "aspirated" consonants, so that "k" comes with a really hard popping noise when pronounced. What sounds specifically make a language feel different from yours? I noticed recently that Irish accents have this weird soft t, so the word for "right" for me (as an American) either ends on no sound, or a hard t sound, but watch a clip of someone saying it in "The Banshees of Inisherin" and it has a soft, breathy quality to it. I have yet to figure out if that sound is even in the IPA, but you bet your butt it's showing up in one of my conlangs.

Also try to limit the number of sounds you use in your language. We, as primarily English speakers, are used to having a wide range of sounds available to us, but 44 is honestly on the high end for distinct sounds in a language. Take away sounds you think of as inherent to speaking, and see how it changes the way the language sounds.

Much ado about syntax

Once you've got your sounds, you can start constructing words and creating your grammar. I'm starting with grammar here, because I usually find my grammar informs how I want to make my words, but the two will go somewhat hand-in-hand. This won't be a grammar deep-dive, but should have enough information to get you started with simple sentences and ideas.

To keep this as simple as possible, you got your word order, your noun modifiers, your verb modifiers, your relationship indicators, and how those agree.

Word order is basically the order in which you assemble your subject, verb, and object. Most simply put, the verb is the action word, the subject is the person or thing DOING the action, and the object is the person or thing RECEIVING the action. English uses subject, verb, object order such as "Polly likes peanuts." Polly is the subject, peanuts is the object. You can put these in any order, but it's useful to know that it is extremely rare for the object to come before the subject. The most common word order in the world is actually SOV, where the verb goes last, so that would be "Polly peanuts likes." While almost all languages have a typical word order, in some languages word order is flexible. "Polly peanuts likes" makes no sense in English, because there's no way to figure out who "likes" what since English word order is fixed. But a language like Japanese clearly notates which word is which, so it's okay to switch it up a bit. If your language essentially says "Polly(subj) peanuts(obj) likes," you could also say "peanuts(obj) Polly(subj) likes," and a reader would still understand the sentence's meaning, so it matters less. Note that languages with flexible word order often also don't need to use pronouns as prolifically. In order to say "I like you" for instance, I need to include the "I" and the "you" because English is a language with strict word order and the verb "like" needs both the person doing the liking and the person being liked, whereas Japanese manga frequently make the joke of someone misinterpreting "sukida" because that's literally just the verb "like." The "I" and the "you" are implied and unnecessary.

There are three simple ways to modify nouns. The first is with adjectives. Does anything mark your adjectives (like "ly") and do you put them before or after your noun? The second is with number. In English we tack an "s" onto most nouns to indicate any plural, while Chinese doesn't indicate plurals on a noun at all, while yet others only modify the noun for a specific number. Modern Hebrew will tack a "áyim" onto the end of time words specifically for "two." "Yom" is day, for instance, while "yomáyim" is two days. Plurals can be indicated with prefixes as well, they do not need to be restricted to suffixes. Finally, you can add noun classes to your language! If you've ever come across a language with genders, like French, grammatical gender is a form of noun class. French marks every noun as either feminine or masculine, whether it makes logical sense or not (the word for cat is always masculine, for instance). Typically feminine nouns finish on an "e" while masculine nouns end with a consonant, but certain words can be either depending on the circumstance. "Serveur" and "serveuse" for instance, both mean "waiter," but the first is only for male waiters, and the second for female waiters. You might say, "wait! We have a separate demarcation for female waiters, that's waitress" and you'd be right. But our use of "ess" to denote females is considered a leftover feature of languages with gender. Grammatical gender is the most common type of noun class, but this can really be anything you want and with any rules for how they're noted and which are which. Some languages use animate vs inanimate as their classification, others strong vs weak or countable vs uncountable, and I've even heard of a conlang that uses "moon and sun" as their classes.

As with adjectives, consider what marks your adverbs and whether they're placed before or after the verb. The main other way to modify verbs is with tenses, which anchor the verbs in time, and moods, which give the verb an attitude of some kind. Once again, Chinese does not use tenses at all, but English has past (liked), present (like), future (will like), ongoing present (is/am liking), and so on and so forth. English actually provides a good example of how tense can be indicated by modifying the verb directly or with a secondary word (liked versus will like). Moods probably sound intense and scary, but I mention them because they're fun AND WE ARE ALREADY FAMILIAR WITH THEM. There's a whole bunch of different types of moods out there, and frankly I don't understand all of them, but when your mother says, "CLEAN YOUR ROOM" she's using the "imperative mood," using the verb "clean" as a command. English imperatives don't change the actual form of the verb, so for a better example, we indicate the "conditional mood" with "would." "If you'd just do this, I WOULD help you." Similarly, we indicate the "hypothetical mood" with "could." "I COULD have fallen to my death." Just like with tenses, you can use separate words OR direct verb modifiers to indicate moods. Japanese directly changes its verbs for various moods. The imperative of the (informal) verb "taberu" is "tabero" for instance, and the formal version "tabemasu" can be changed to "taberudeshou" in what they call a "potential mood" to indicate that something is likely, but not necessarily true.

When I say "relationship indicator" I just mean things that indicate a relationship between other words. "In" "on" "under" "after" "towards" "of" "for" "from" "throughout" "until" "with" and "ago" are all words that note some kind of relationship. When you say "the paper is on the table" you indicate a specifical physical relationship between the paper and the table, and "I ate AFTER exercising" indicates a specific temporal relationship between the actions of eating and exercising. I'm also putting possessives here, because it's a sort of relationship, in my opinion, and once again, recall that any of these relationships can be indicated with separate words or direct modifications. "Kit's plushy" involves a possessive marker on "Kit" to indicate who the plushy belongs to, but Japanese and Chinese only use separate short words to indicate possession ("no" and "de" respectively, "my dog" is "watashi(me) no inu(dog)" in Japanese, and "wo(me) de gou(dog)" in Chinese). Where you PUT the relational markers is not always going to be exactly the same as in English. For instance, we say "I talk ABOUT that" whereas Japanese does the opposite "I thisthing NITSUITE talk" with "nitsuite" being the "about" word, and the thing talked about going first.

I put case agreement last because it combines many of the previous elements, but its concept is very simple. With every classification and modification, there comes the option to make things match each other, basically. We do this a little in English. "I am" and "we are" possess the same tense and mood and verb, but the verb changes form to match the plurality of the subject. "I" is singular, and its "to be" verb is "am." This changes to "are" with "we" because "we" is plural. In French, "a man" is "un homme" while "a woman" is "une femme." In this case, "un" matches the gender of the noun it's attached to. In one of my conlangs, the subject of a sentence is given a "d" at the end of the word, and every adjective attached to the subject is given the same ending, but the verbs aren't affected by the nouns in any way. The extent to which things agree is entirely up to you.

Word construction

When you make words, for the most part you can go for however you want them to sound, but it can be helpful to keep a few things in mind.

Firstly, in terms of sounds, do you have any rules in mind? It's fine if you don't, but English definitely does, so it'll color how you construct your words if you're not careful. In English, "ng" can't be used to start a word, for instance. Neither can "ts" (think "rights"). One thing I like to do is make it so that if the letters "n" and "g" are next to each other, they're still pronounced very separately, for instance. So in English, "ingot" is really "ing-git." The n merges with the g to form a "ng" sound, whereas in one of my languages, it'd sound more like "in-git." Similarly, English requires "tp" to sound very separately so "cut-purse" simply represents the "t" sound by cutting off the vowel before the p (a similar effect occurs with padparasha), but the indigenous language Nuxalk contains a word that starts with the sound "tpya," so the t explodes directly into the p. Some languages don't require syllables to have a vowel sound, so a combination of consonants like "sqw" or "kst" can stop suddenly and be considered its own syllable.

Secondly, think of more complex ideas as combinations of smaller words and ideas. I've just used a ton of adjectives in the previous paragraph "definitely" "separately" "similarly" and these ones all share the suffix "ly" to indicate that they have been turned into adjectives. "Helpful" and "careful" can be broken down into respectively "help" and "care" "full." Even the word "explode" combines the prefix "ex" meaning "out" with "plaudere" from Latin meaning "to clap." Not a fan of lots of suffixes and prefixes? Large portions of more complex Chinese words are constructed like "birthday" - "birth" "day" combined. And in Japanese the word for "free" (financially) is "無料" which literally means "no fee." Of course there will be some ideas that need their own word and sound, but there are a lot you can make by smushing multiple concepts together into the same word.

Thirdly, break down words into their separate concepts, and mix and match them. Rather than making words by combining concepts, as I mentioned above, what I mean here is to recognize that in basically every language, a lot of words are doing double duty. The questions "how did it go?" and "where did you go?" both use the verb "go" for instance, but in the first case, it indicates a state of being, whereas in the second, it indicates the physical action of travel. Or "have" normally means to possess something, but when you say "I have to" it has nothing to do with possession, and instead indicates that you must. Sometimes these words are straight homonyms ("bat" the stick you swing at a ball vs "bat" the animal), but a lot of times words take on additional adjacent meanings without our even thinking about it. Consider these separate concepts and whether they have separate words in your language. In the reverse, try to think of words you normally look at separately and combine them into one. The Japanese word "笑う" is used for both smiling and laughing, and is the only proper verb that can be used for either action (though you can say someone "let out a smiling face" to specifically indicate someone smiled and didn't laugh).

And lastly, think about words and especially phrases, in their cultural contexts. Words do not exist in a vacuum. Almost all languages have varying levels of formality, for instance, but Korean - a language developed in a culture where heirarchical status is really important - has separate pronouns and even sometimes separate verbs depending on who you're speaking to or about. "I" or "me" is "저" when you're speaking to someone you don't know well or who is distinctly higher than you in some way (grandparent, boss), because this is the humble form. Whereas it's "나" among friends or like... younger siblings, lol. And the verb "to sleep" is "주무시다" when you are referring to someone higher than you DOING the action, but "자다" for everyone else. You tell your grandparents to "sleep well" with the first version, but tell your boss or buddies that you are "going to sleep" with the second.

Swear words will depend strongly on what your culture considers taboo and how the word is perceived. "God" and "damn" were very significant swear words in English back when Christianity was taken very seriously by English speakers as a whole, while "cunt" was widely used in medical documents in the Middle ages. Legs were considered so private in the Victorian era that using the word "leg" itself was considered swearing, and the word "occupant" in the 1600s was a euphemism for prostitute, because people had started to use "occupy" to exclusively refer to having sex. If animals are considered unclean or debased, they might also feature widely in curse words in your language. My impression is that a lot of swear words tend to revolve around animals, religion, or the physical body, but they can also refer to certain ailments or disabilities such as "retard."

As I said in my "Language in Worldbuilding" guide, try not to think of the speakers of your conlang as deeply foreign and exotic to you. I don't know if this is a general trend, or just something I started with and kicked because it's gross and fetishy, but there can sometimes be a tendency to think of your conlang speakers as especially deep compared to us. There's this moment I think is hilarious in Avatar (the blue one) where the protagonist is being taught the Na'vi language, and his colleague tells him the greeting is "I see you" not just a physical seeing, but as in "I see into you" a sort of "I see your essence." Whereas in every actual language on this earth I know of, greetings are way more basic and practical. The English "hello" is derived from noises meant to call attention to oneself "HEY THERE" basically. In Chinese the classic "nihao" is literally "you good?" (though obviously with a less flippant connotation). Korean "annyeoung" actually means "to be well or at peace" and the entire phrase in its literal meaning is "please do well." Among friends, you don't even bother with that, you just ask "밥 먹었어?" which literally translates to "you eaten rice/a meal yet?" When you're developing a conlang, it's obviously okay if you want to do this sort of thing as a way of indicating how deeply spiritual your forest elves are, or whatever, but I personally find something really meaningful about looking at your conlang as if it contains the essence of actual real life human beings. There

are cultural differences among different peoples, but there's a universality to what matters to us: health, security, power, personal identity, the people we love, having beliefs about meaning and purpose, and how grounded our lives are in those things, so make your languages grounded, too.

Testing, testing, one, two, three

This may perhaps sound obvious, but I find I need to remind myself of it frequently: unless you are a legit linguist who knows what you're doing (buddy, why are you reading this? Also will you please take me under your wing as your protégé?) I find that the best way to learn and develop your own language is to keep working with it. In particular I'd suggest trying to translate things into it, or write directly in your new language. The more complex ideas you try to portray, the more you'll notice gaps in how your language functions, and how you want to fill them.

If you want to go further into making a conlang, I'd definitely recommend the youtube playlist

How to Make a Language by Biblaridion. He goes through each stage with an example language. I find that he has the curse of knowledge, and is a tad hard to follow with all his linguistic terminology, and also that he focuses very hard on constructing a language MEANT to be a hardcore natlang that other linguists will accept as such. He goes very deep into how to make your language evolve for instance, and I don't think that's really necessary for most conlangers at least at the level where we just want to have fun (like me), and he insists that writing system development must go last, when I usually start with a script after I've chosen my sounds, because I for some reason work better backwards than forwards, LOL, but it's still a great resource, even for beginners. There are so many complicated facets to language, and I haven't even begun to discuss them all. I debated adding in a mention of passive voice, intransitive vs transitive verbs, and don't get me started on ergative-absolutive vs nominative-accusative languages, but with all this, the level of detail you go into is up to you! The best thing you can do with any language is have a good time with it.

A note on language scripts

"Script" here refers to the glyphs used to write/represent meaning or sound in your language. I think it's fair to say most conlangers start out with their earliest languages thinking more about replacing the letters to a language they're already familiar with. My first ever exposure to language showing up in a story was in Artemis Fowl. I was the nerd who figured out what letter each symbol represented, from the excerpt in the first book, and then translated the bits at the bottom of each book following that. As a result, the first few times I tackled making a language, it was largely cyphers just like that. It can be really tempting to just start drawing symbols and assigning them different sounds. This is perfectly valid, goodness knows I've done the same! But it's probably good to know what types of writing systems are out there, and other things you can consider when you make a script.

Proper linguists would probably shoot me for this, but I find the easiest classification to understand is as follows:

1.

Logogram: Each symbol represents an idea. Logograms are also referred to as logosyllabaries, because most of the time, each symbol also represents one syllable. Chinese is basically the last surviving logosyllabary. For example, the symbol 天 refers to the sky (among other sky-ish things), but also represents the sound tian. When a speaker sees the character, both the sound and the meaning are evoked. None of the following classifications include an inherent meaning to their symbols, instead all representing sound in some way.

2.

Syllabary: Each symbol represents a single full syllable. Japanese か sounds like "ka" for instance. This is why haikus work in Japanese without the type of ambiguity that occurs when people try to write them in English. Each syllable is well-defined and represented with a single symbol.

3.

Alphabet: Each symbol represents either a consonant or a vowel separately and with what they call "equal weight." English is an easy example. The letter e (a symbol representing a vowel) is given the same amount of space and emphasis in writing as n (a symbol representing a consonant).

4.

Abugida: Each symbol represents a consonant with one vowel implied, UNLESS something is added on to indicate the vowel. Wikipedia cites the Indian Devanagari as the most well-known example, but my bet is that most people (myself included) aren't familiar with it. Basically, प represents the syllable "pa." To make it represent a syllable with any other vowel sound, something has to modify the base letter, like पि (pi) and पे (pe). All other consonants follow suit - base letter represents the consonant + "a" and modifications indicate other vowels replace the "a."

5.

Abjad: Each symbol represents a single consonant. Vowel markers (whether full sized or just modifiers of the consonants) do not exist or are almost completely optional, and have to be inferred. Most modern abjads are considered impure because they have some vowel markers. Arabic is the classic example and it has both optional vowel modifiers and one vowel sound that's written as a consonant. (In fact, the word abjad itself comes from the first four letters in the Arabic "alphabet" aleph, bet, gimel, and dalet.)

The categories above are helpful to think about, but you definitely shouldn't feel restricted by them. English technically classifies as an alphabet, but it's not as though it's actually possible to correctly identify the sounds associated with a word purely through the written text. Of course there's Japanese which uses a combination of two separate syllabaries and a logogram, and Korean's writing system is what I'd call an alphabet, but it's apparently messed up enough that some linguist added the classification "featural" to describe it.

You also want to decide reading order as you're developing your script. English uses left-right top-bottom reading order, where you read on the horizontal line from the left to the right, and then down. Japanese can be written that way, but is also commonly written top-bottom right-left, where you read the rightmost column top to bottom FIRST, and then begin moving column by column to the left. You can mix and match that a bit or, if you're feeling really spicy, you can use something called boustrophedon, where you read the lines in rows, but each row alternates direction. Though rare, some very very old writing systems were discovered that go in a spiral, either starting from a central point and going in a circle around the start, or the opposite way, starting on the outside and writing in a circle inwards. The writing direction you choose will inform what your script looks like. The old Mongolian script can only be written vertically, for instance, while Arabic can only be written horizontally, both because they connect their words through some sort of baseline. Latin and Cyrillic probably can be written either way, but are difficult to read vertically, while the East Asian languages contain their sounds well enough in square-ish sized boxes that it's easy to write and read them any direction you like so long as it's square in nature.

If your conlang is meant to be a natlang, usually it evolves from something simpler which in turn usually came from more generalized pictographs, so sometimes it can be fun to think about what that proto-writing looked like and how long it's been around to change into is current form. What did your ancient people have available to write on and how does that affect your writing system now? What things got preserved and why?

It's also good to think about how words and sentences are separated. What sort of punctuation does your language use? Sentence markers are probably the most important and common, but question markers, quotations, and hesitation markers like a comma are also found in plenty of languages. Are words spaced in your language? In English, we separate every single word with a space, but Korean puts spaces after short phrases, and Japanese doesn't use any kind of spaces at all. Do your letters have different forms? The only real example of this I can think of is letter case (uppercase, lowercase). If so, what is it used to denote? Does it have meaning at all? I personally never put letter case in my conlangs, but mostly because I never figured out what good they were even in English. Does your script have a decorative or cursive version? Those can also be nice to add, though I intentionally try to develop most of them with the assumption that the one I'm working on is computer standard perfect.

There is no possible type of script you can think of that the world hasn't developed already, so my number one piece of advice for you when developing a script is to relax and have fun. Be creative and focus on enjoying yourself. The questions above are how I develop my script in a deeper way, because that's how I enjoy doing it, but if you're all vibes and pretties, there's nothing wrong with that either.